ON ABUNDANCE

7/24/25

Several years ago, our architecture practice, ONYX, was leading an apartment project through the entitlements process. The front yard setback of the project site was prescribed to be an average of the setbacks of surrounding building faces—usually between 20 to 25 feet. The problem with this particular site was that it was adjacent to a very large surface parking lot, so the "average" calculated setback was more than 50 feet from the sidewalk. This calculation was certainly not what the City of Pasadena, we as architects, or the client wanted. Yet staff decreed that a full environmental evaluation would need to take place, requiring consultants and hearings, costing many thousands of dollars and a year's time—all to confirm what we already knew. Logic could not prevail over a system that promoted high costs and scarcity.

I've enjoyed reading the book 'Abundance' by Ezra Klein and Derek Thomson; I'm not the only one- The book has gotten a lot of attention in policy circles and among urban development enthusiasts since its publication. Its compelling arguments about scarcity versus abundance mindsets have resonated with many readers across the political spectrum.

It hit home because it summarized years of frustration resulting from the battles to build and improve good cities. Klein and Thomson articulate clearly how regulatory barriers, NIMBYism, and outdated zoning and environmental laws have collectively hindered our ability to create affordable housing and vibrant urban spaces that benefit everyone, not just a privileged few.

As with anything that cuts through deeply held opinions and interests, there have been a lot of critiques on what the points Klein and Thomson try to make. Some critics argue their solutions are oversimplified, while others suggest they don't adequately address equity concerns or environmental impacts. Yet the conversation around the book has been as nuanced and complex as the issues it tackles.

An opinion piece from the Washington Post by EJ Dionne Jr. suggests the fervor the book has created- here’s a quote:

“This accounting by no means exhausts the slings and arrows that have been hurled Abundance’s way, but the energy of this debate suggests that its disciples have struck a nerve.”

Simplifying the process of building is bound to ruffle some feathers—certain groups would lose influence, and some consultants might see their fees dwindle.

Most of us in architecture and construction want to do meaningful work, yet the processes are beyond burdensome, overreaching the public good they try to achieve.

Ordinances and procedures—especially the ones that shape the communities we’re able to create—must be continually re-examined, improved, and streamlined. If not, we’re left with the stagnant, expensive ways we currently build our cities and infrastructure.

Abundance has certainly sparked conversation—which is a good thing. It may even have set needed reforms in motion. For the first time since the 1970s, California’s original environmental law, CEQA, has been amended to allow for faster housing approvals. Governor Newsom even name-checked Abundance when signing the legislation.

Regulation and process are vital for creating fair, livable places—but they shouldn’t stifle good design or overwhelm creativity. There’s a lot to do to fix this. Let’s keep these conversations alive, especially in these divisive times. How can we make it easier to build sustainable, equitable, and beautiful cities? Let’s figure out how to do more to get the great cities we deserve.

REBUILDING

1/30/25

I live uncomfortably close to the horrific fires that hit the Southern California area this January 2025. Specifically the Eaton Canyon fire, affected thousands of homes and businesses in Pasadena, and primarily Altadena. Some have died. It’s been an awful event. It’s the kind of event that really makes you re-evaluate what we do with our built environment.

In spite of the shock, people who live in or near the fire areas of Southern California want to build back. Like it was, and as soon as possible.

A very worthwhile goal. Unfortunately, there are obstacles.

So here’s a prediction: With the rebuilding, there will be great achievements and great things to replace what was lost.

But we won’t really replace all of what we've lost. I think we’ll loose a lot of the finesse, scale, and fine grain of the modest multigenerational neighborhoods; the integrity created from simple but well conceived structures conceived by architects or small designer/builders.

But can we at least expedite the replacement of these neighborhoods? Unfortunately, with some noticeable exceptions, this will take decades.

In addition, the pressure to move these neighborhoods upscale will be immense. Many lower to middle class families, with multi-generational roots, will be edged out by development for wealthier people.

We don't build like we used to, and for the cross-section of people we used to. Our best intentions, and the implementation of them, have unwittingly become the enemy of the good.

We've lost the building ethics we had for a bit more than half of the 20th century and before. Ethics that allowed for appropriately sized, delicately detailed, and economic to build residential and like commercial buildings. When we rebuild, we’ll end up building luxury homes, and subsidized multi family residential to some how cover what we’ve lost.

Back 70 or so years ago, a family could afford to hire an architect to do work for a couple weeks to do a set of plans. Small builders were conversant in building appropriately, suitable to making a neighborhood that could be loved. Sash and doors were constructed on site or came from a local workshop. Carpenters and Masons knew how to construct their components quickly and elegantly. Municipalities were able to check and approve plans often within a day. Simple and good ways to make good things.

Those days are gone. For all the good reasons, for complications those reasons create, and the thoughtless piling on, those days are gone. Maybe we’ll discover we were actually losing something?

Consider these complications— again for good reasons, to solve what we thought were a series of (apparently) unconnected problems:

Comprehensive envelope and insulation design, carefully checked and implemented

Accessibility issues, even within the most simple structures; all carefully checked and implemented.

Parking requirements, more regimented setbacks, and other regimented planning dictates.

Structural and geotechnical design issues— all to keep us safe, but validated in ways to be painfully laborious rather then professional and expeditious.

Sustainability design issues— all to help safe the planet, but validated in ways to be painfully laborious rather then professional and expeditious.

Community design review.

Great! These are important things, some more, and some less important then we think they are. But everything will be a lot more expensive and it'll take a lot more time than it once could. And none of it will have the delicacy and appropriateness of what was done originally.

There are really great architects and builders out there. Great stuff gets done, and some great stuff will be built in the place of that we have lost. Miracles will happen in the course of expediting repairs. But, with all the complications we've added, we’ve made it much harder to come back after a tragedy like this. After year upon year of layered and siloed processes, we realize that no one has paid any attention to these basic ethics that allow for us to build for every economic group and make great neighborhoods in the first place.

No matter how you feel about climate change, devastating events that will wipe out large portions of beloved communities will occur more often, and be more severe.

It is a responsibility of every government, and every advocacy group to understand what has been lost and why we need to make better ways to make communities to build and rebuild.

We must:

Find, establish and lift up trusted partners in the building and design industry.

Our processes must be greatly simplified; there are better ways to identify and verify what needs to be done.

Advocacy groups must be must absolutely understand other concerns besides their own in the building of communities. Simplicity and beauty are really as important, as our other concerns.

I'm hoping for the best as we rebuild the Palisades and Altadena. Again, some good things will happen, but I fear we’ll will lose many opportunities for equity, accommodation, and beauty, the intangibles that make for a loved community, all in the name of moribund and contradictory processes.

Let’s take this opportunity to start to to break down the advocacy Silos and the inertia of over-complication.

We know what to do. Let's communicate. Let's build a accommodating sustainable and beautiful neighborhoods and cities. Let's innovate. Let’s not waste time and effort.

thoughts about cities

Check out my YouTube Channel

Please drop by periodically, and thanks for reading and contributing to the conversation!

TOWER HOUSE | STUDIO OH SONG

YouTube Series: CHARETTE

12/09/25

THE PENDULUM OF PRIORITIES

The reason we build cities is to facilitate commerce and our culture. And to provide places to live for the people who participate in this commerce and this culture.

If it’s too hard to build places to live, we have a housing shortage. So some people have to live in crowded conditions, or they have nowhere to live. The commerce and the culture suffers.

So after much turmoil, we find ourselves hastily building more housing, pushing aside the difficulties getting roofs over people’s heads. And, because we have been hasty, we have problems… crime, lack of opportunity, lack of beauty. So then we hastily decide, no more hasty housing, and we hastily tear down places that are seen to contribute to the difficulties, instigated by the hasty decisions we previously made. Surprise, surprise, we again have a shortage of housing.

We’re in a cycle of making it too difficult to build enough, counter-balanced by another cycle of going too haphazardly to build well

Our haphazard building ethic has resulted in increased personal isolation, even in the most crowded places. Social erosion develops from the fact that those who have little, suffer from the lack of housing, and the lack of any quality of life. Increasingly, neighborhoods can lose their support systems and character. Worse yet, the good neighborhoods that have survived despite the odds, still have everything working against them, and get bulldozed and replaced.

Sigh!

Happily, there are some thinkers and designers seeking solutions out there!

Recently, an Urbanarium Decoding Density ‘missing middle’ housing competition in Vancouver, Canada captured our attention by presenting particularly compelling ideas for architectural innovation. This initiative sought solutions that bridge the gap between single-family homes and large apartment buildings, addressing both the greater housing needs and community-building potential.

Similarly, the growing single-exit movement for multi-story residential buildings has emerged as a catalyst for reconsidering fundamental housing design assumptions. This approach offers different pathways for architectural expression while potentially improving space utilization and construction efficiency without compromising safety standards.

This inspired us here at ONYX.

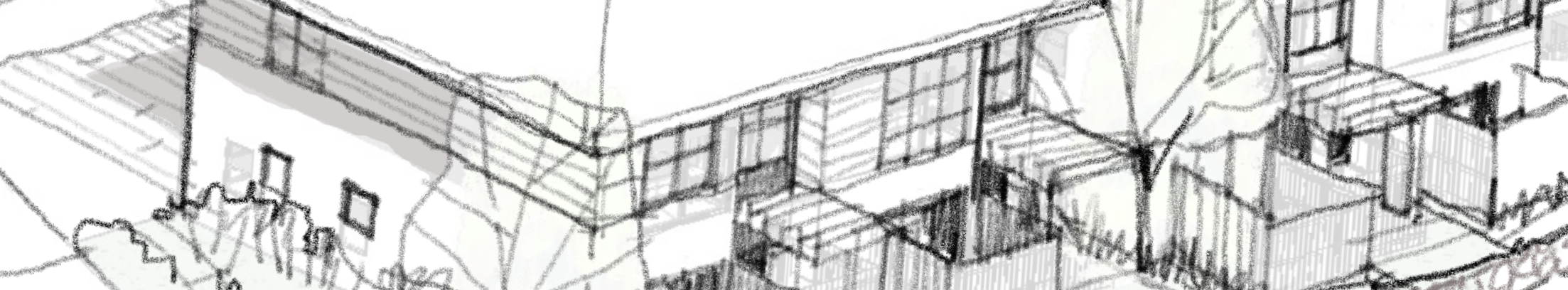

In response to these concepts, our office organized into distinct collaborative teams, each tasked with developing comprehensive designs that thoughtfully integrated both the pragmatic efficiency of the single-exit concept and the community-oriented principles underlying missing middle housing typologies.

What we’re doing here is just dipping a toe into the water, yet the teams explored, developed, and tested residential building configurations that deliberately challenge and transcend the limitations imposed by outdated prescriptive zoning practices that have dominated urban planning for decades. Our approaches prioritized adaptability, community integration, and sustainable living patterns.

THE CHARETTE

The site is 1.86 acres in northwest Pasadena. It was formerly a building supply store in a decades-old mixed-use neighborhood. Each team’s designs should contain about 100 living units, along with commercial and community spaces to support the neighborhood. Outdoor spaces are important to be included, and designed for beauty and activity that are integral to the building’s function and design.

Our participants broke into three teams. These teams have been consistent through the different charrettes we've done. We asked each team to maintain the same themes and design approaches they've used in previous charrettes, approaches such as:

LIGHT

PROCESSION

RELATION AND SUPPORT TO SURROUNDINGS

PATTERNS

SYMBOLS

GEOMETRY

Along with these consistent approaches, participants were asked to use the concepts presented in the Urbanarium Decoding Density competition as integral inspirations for their designs.

The explanations and debates amongst the teams was friendly but vigorous. What do these new ways of thinking about housing really mean for our design process?

We’re learning to do more then just designing housing units and places to put people’s cars. We’re learning how to create communities to make better neighborhoods and better cities. All of us involved in the practice of designing and building places for people to live need to do a better job of thinking about how people exist and thrive in what we have provided. How do the people we are designing for get the things they need, how do they meet other people, how do they maintain a feeling of well-being and security, and how do they make a living? Our efforts suggest that we can do a better job creating individual projects that create microcosms of the neighborhoods and communities that we really want; and if this is done many times over, it would be transformative in the financial, and social well-being of the cities where we live. We at Onyx looking forward to continuing these charrettes as a means of inspiring a deeper thought process when we design in the future.

YouTube Series: BACKGROUND OR ICON?

I think that these producers of icons manage (often but not always) to somehow relate their work to their surroundings. In two ways:

First, As a precious gem, something that sets itself off from its surroundings— or—

Second, By accidentally providing the requisite qualities that contribute to the larger collective architecture of the outdoor room.

YouTube Series: A VISIT TO AMSTERDAM

Blending the inter-modal transportation systems can be messy. As the Dutch work on their cities, my observations tell me that they are making the effort to make things logical, safe, and attractive. Observing the newer infrastructure tells me that the City is concerned with making it quicker to ride a bike, and easier to park it, safer to walk, and more beautiful for everyone. Lessons are learned and corrected with each new project.

YouTube Series: LOOKING FOR THE PERFECT STREET

It's easy to overlook the importance of well-designed streets. We shouldn’t be doing that. A great street is the ultimate work of architecture.

SHARING IN THE CITY

Yet there remains a disappointing and exasperating clash between the creation of buildings, and with the processes that occurs in how we envision cities.

TWO SHIPS PASSING IN THE NIGHT

Often we designers think of a building, or collection of buildings, in pure isolation. Our creations are planned and composed in isolation within the boundaries of the land provided. We solve the specific aesthetic and functional issues within the envelope allowed by the municipal authorities.

THE CITY IN TIMES OF COVID

Turns this ‘necessity’ birthed some interesting ‘inventions’— the ‘hacks’ created by this necessity have been kind of cool. The necessity? Restaurants and Bars could no longer operate safely in their former mostly indoor environments. Performing arts practices and performances could no longer take place inside. Education could no longer take place in its traditional environments. Everything that could not be handled by a Zoom call needed an an alternative involving fresh air in order to resume.

SELECTED ARCHIVE POSTS: